Fortunately, 47 finds Olivia safe and sound. Unfortunately, it’s not long before the ICA tries again. Olivia barely fends off one of their cyberattacks, and it starts to sink in that Berlin only bought them time. 47 is one fugitive. The ICA is the ICA. Absolution proved that they’ll hound him to the ends of the earth. For an employer who owes most of their success to us - and who we’ve saved more than once - they’re remarkably ungrateful. That’s neutrality for you. 47 may be their best asset, but he’s still just an asset when the rubber meets the road.

noir blinds.jpg

All the while, Arthur has been wearing Diana down, preying on her need to get justice for her family. He sees a potential protégée in her cunning and intellect, but she’ll never join him as long as she’s on 47’s side. Three games in, he’s not getting the results that he hoped for. She’s not taking any of his bait. He’ll have to force the point. Arthur reveals outright that 47 killed her parents, then warns her that fighting power as an abstract is futile. He offers her another choice: take that power for herself. If she became the next Constant, she could shape the world to her will. At this point, Diana appears to earnestly think about it, though we know we can’t judge her on appearances alone. She’s a cipher, and Arthur wouldn’t be the first villain she’s strung along. But it’s an ugly truth we’re talking about. This time, things could be different.

47 makes up his mind. If he ever wants to stop running, he’ll have to take the ICA down again - this time, for good. The Agency derives their power from their secrecy, so exposing them is the most efficient way to ruin them. To initiate the leak, 47 infiltrates the ICA’s data headquarters, a modular base stationed in Chongqing. Once in, he’ll have to disable the archive’s biometric lock by killing the facility’s heads in a short amount of time. The mission oozes cyberpunk, from the gadgets to the city lights, and it dovetails nicely with the series’ speculative elements. But good cyberpunk is about people first, and the level’s tech-noir heart lies in the heavy sorrow that hangs over the neon night. We never wanted it to come to this. The ICA used to be our home. But they’ve made their choice clear. It’s not murder. It’s self-defense.

For a game about autonomy, cyberpunk is a great callout. The genre has always grappled with technology’s dominion over human will. Hitman has Hush, the ICA’s cybersecurity chief, and, by a strange coincidence, Olivia’s former mentor. With Hush’s reclusive nature and his link to our new friend - well, Lucas’ friend, anyway - we might expect him to dress like her. Instead, when we finagle our way into his very well-guarded lab, we find him in a beige suit that suggests something more disturbing. Hush’s file reports that he cut his teeth sowing discord among dissidents in Khandanyang, a fictional dictatorship. When that went sour, he pivoted to helping criminals cover their tracks, and the ICA decided they could put his talents to use. Hush’s suit plays off that history, showing that he approaches his craft not as a plucky hacker, but a government official. Even if he wasn’t a fan of the regime, it paints him as a dispassionate accessory to it. No wonder Olivia hates him so much.

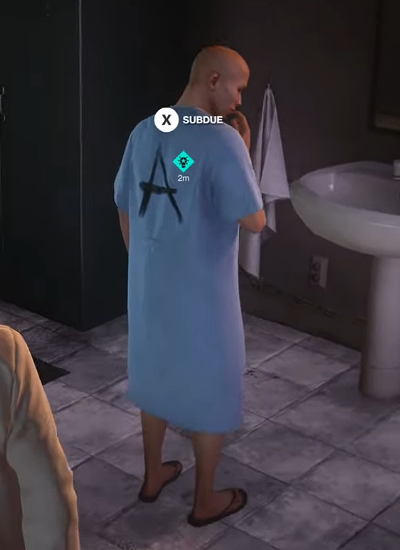

She’s more right than she realizes. Before we even meet Hush, we find flyers for his project, the “Future Progress Initiative.” Some of the impoverished citizens are skeptical about it. Others need the money so badly, they have to sign up. Through a mission story, we learn what the study really is: a cruel, potentially-fatal experiment in puppetry. Hush has put the ICA’s deep pockets toward a device that’s supposed to control targets’ muscles through brainwaves. It doesn’t work - his tests kill the subject almost every time - but that hasn’t stopped him from trying over and over again. We have no idea how many lives he’s thrown at this thing. He may not either, seeing how he dresses them alike. Their jumpsuits and hospital gowns rob them of their personhood, reducing them to useful bodies like an asylum full of clones.

When we descend into the ICA’s sprawling facility, we find out why he might be so desperate to finish it. Hush nurses a nasty rivalry with the ICA’s archivist, a waifish computer whiz who shares his digital god complex. Imogen Royce is a misfit who reinvented herself online, building a following around her ideas about the machine-state. Her file says she grew up in Hong Kong, which likely explains her blue cheongsam. What she’s done to her body itself merits more interest. Imogen has gone to great pains to look like a cyborg, and from the patterns on her chin and forehead, that might be literal. Their ridges suggest it’s scarification, which is not for the faint of heart, and extreme even for many body-mod enthusiasts. She’s also shaved her eyebrows, and while her bangs bewilder me, she seems to have twisted or braided most of her hair into cords. Textured hair types suit that style. Imogen’s does not. It’s a lot of effort to appear constantly “plugged in.”

She sort of is, if you think about it. Imogen is a behavioral analyst, and she runs her archive like a dystopian ARG. Like Hush, Imogen has used ICA money to innovate, designing a software that predicts her employees’ movements. Unlike Hush’s invention, it’s freakishly accurate, down to their emotions and actions when she fires them. She spends all day at her screen assigning them repetitive tasks, then introducing stressors to tune the procedural data. She’s always watching. She always knows where her pawns will go next, and that starts to knock uncomfortably on the game’s fourth wall. Imogen is the series veteran in pursuit of the five-star mission score, the one who’s loaded so many saves that she’s memorized the NPC loops. She derives her sense of achievement from anticipating her targets’ moves, toying with them to shift their patterns, and dispatching them. She’s us.

And what does that say about us? For a minute, Hitman drops the murder fantasy and asks the player to look in the mirror. We are a little messed up for enjoying this sort of game, aren’t we? Have we been complicit in controlling 47 too? That may be beyond the scope of this project, but one thing’s for sure: it’ll feel all the more poignant when we set him free.

In the wake of the ICA’s breakup, things take a turn for the strange. Diana appears on an airport camera with a Providence pin. Olivia is sure she’s betrayed us. 47 knows his old friend would never let herself be recorded without a good reason. They follow the breadcrumbs to a vineyard in Mendoza, where a high-ranking Herald is celebrating his retirement. As soon as 47 meets Diana there, she fills him in: she’s going to accept Arthur’s offer, then destroy Providence from the inside. Plot seeps like blood through The Farewell, from the ambient dialogue to the kills. The narrative - and emotional - stakes have never been so high. Both Diana’s life and loyalty are on the line. All we can hope is that we won’t have to do the unthinkable.

Diana will have some hurdles to clear before she gets the offer, though. Not everyone at the party is convinced she deserves it. I mean, she did help us assassinate a bunch of their people. To help, we’ll have to kill the other frontrunner: the party’s host. Don Archibald Yates is hanging up his legal hat after decades of defending dodgy corporate interests. He also torpedoed his wife’s career to save his own, and it’s implied he’s resorted to murder to win cases before. Remember Ken Morgan? He and Don founded the same New York firm. Imagine having to eat dinner at Dorsia with those guys.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that Archibald is his first name, and people call him Don out of fear and respect, like Don Vito. The Partners’ legal counsel is trying very hard to command it, and it’s all down to his white tuxedo and boutonniere. The white dinner jacket emerged in the 1930s as a warm-weather tuxedo, fitting for tropical escapes. With black pants, it remains a handsome standard to this day. With white pants and a big flower, it becomes a bandleader look. From his toast to throwing the party at his own vineyard, Don has ensured that he’ll be the center of attention all night. Retirement parties tend to be something you throw for other people. Don’s doing his own, and he wants everyone to know he’s the star. Maybe he thinks that if he entertains Providence well enough, they’ll forget about Diana and rally behind him instead. Or maybe he’s just a narcissist. Fernando Delgado and Pablo Ochoa’s white suits may have gone upscale, but they haven’t lost their flashiness.

Meanwhile, the spy that Arthur has sent to keep tabs on Diana stews with resentment that Don edged her out of the race. Tamara Vidal believes the world should belong to the best, and she’s gotten closer to holding office than Don ever did. After a torture-happy few years with the CIA, Tamara founded a far-right party, Future Federation, back home. Arthur liked the cut of Future Federation’s jib, so he plucked her out of politics and made her his top aide. Tamara has turned out in a blue cocktail dress with white opera gloves - the colors of Providence, but also of the Argentinian flag. The dress is one-shouldered, and it has a toga-like drape in the back, which evokes the Roman culture that enchants authoritarians. These details point to a hard-nosed, image-savvy stateswoman who’s well-versed in using fashion to play to a room.

All of that would make sense on its own. But one piece of Tamara’s design challenges our assumptions: the large feather tattoo on her calf. Tamara’s dress is short, so she’s not trying to cover it up, and that casts a curious light on her campaigning days. See, right-wing movements are often socially conservative. While her concern is economics, the “traditional values” tend to come, too. A tattoo would clash with that image of old-fashioned femininity, and the corporate elitists would consider it lowbrow. However, these things are changing. Ideological glaciers will shift if they need to market themselves to a younger crowd. Particularly radical groups - Tamara’s file describes her party as “crypto-fascist” - use tattoos as a badge of membership. Of course, we can only speculate about when she got the tattoo, but who knows? It could have been Future Federation’s symbol. With her “dash of transhumanism” in the mix, Tamara could represent a terrifying new breed of oligarch.

Which makes it all the more nerve-wracking that Diana has to cozy up to her to pass Arthur’s test of allegiance. At this point, Diana is desperate. She’s working with what she’s got, so she makes moves that are at odds with the handler we know. She plays an abnormally hands-on role in 47’s work, setting Tamara up for unusually brutal deaths. If the player enlists a sniper, she lures Tamara away from the crowd under the pretense of sneaking a smoke, a reckless habit that we know she quit years ago. (Seriously, ma’am, did we not just blow up Janus’ oxygen tank?) If Don backs her into a corner, she even stabs him herself, bloodying her hands for the first - and I suspect last - time. These actions add tension and ambiguity around her motives. She’s willing to do anything to pull this off. Has Arthur changed her after all?

Her outfit suggests he hasn’t. Amid all the chaos, Diana has put together a look that remains true to herself. She’s chosen a sheath dress that combines a dramatic thigh slit with a plain, modest V neckline. That accomplishes two things. First, it satisfies the rule that if one half of a dress is revealing, the other half should provide coverage to balance it. That’s a classic principle that matches her earlier capsule look, creating a unified visual language within her wardrobe. Second, it shows that she’s not afraid to be glamorous, but in an age-appropriate way that speaks to her background and role in the event. While she may be the talk of the party, unlike Don, she’s not trying to be. No baronet’s daughter or veteran lady of intrigue should. With her gloves and minimalist jewelry, the look assuages Providence’s fears. She’s comfortable in her power, but not there to usurp them.

But we know that gloves protect the hands from dirty jobs, and that’s what Diana really has to do to earn Arthur’s trust. She poisons 47 with a neurotoxin by touching him and gives him a bitter earful once he’s too weak to fight back. How she knows what he did. How he’s always been a tool. She also waits until the Providence guards are close enough to hear it. Diana has used her clothing for subterfuge since Blood Money, and the color symbolism that runs through the reboot has one last laugh. We realize that, despite the poison and villainous posturing, and despite her origami pin, she still wore a black dress. Black is 47’s color, not Providence’s. She was flying our flag all along. She’ll make it right. She always does.

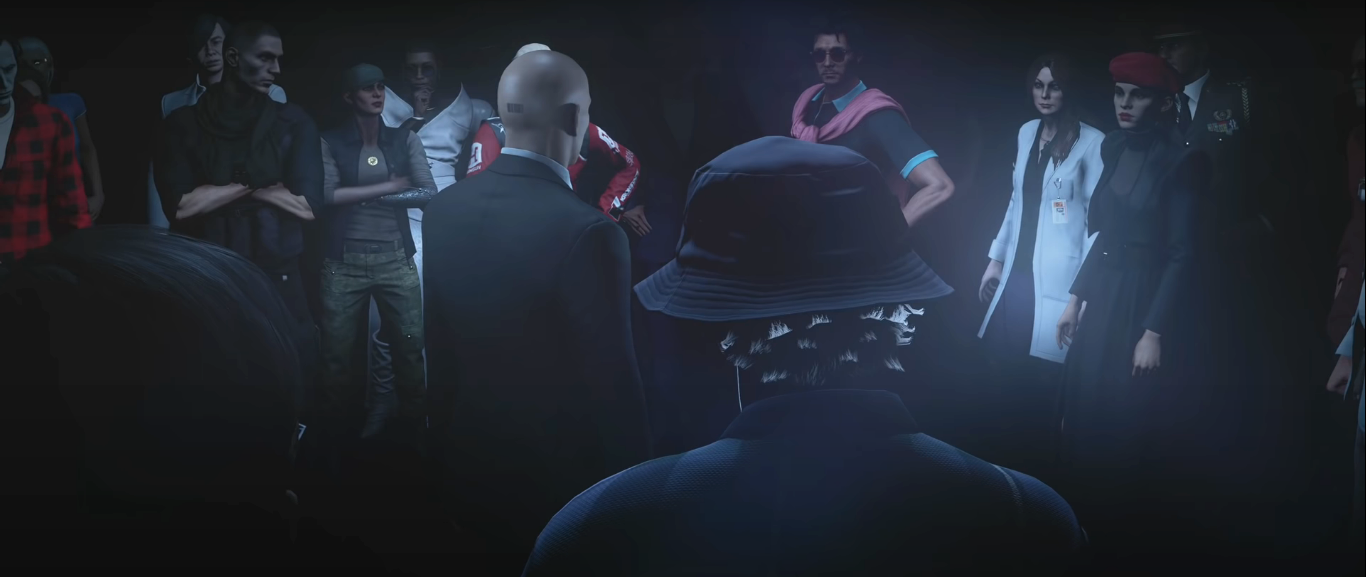

After that, 47 loses touch for a while. He retreats into the shadows of his neurotoxin-addled mind. The player follows him down a Contracts-esque rabbit hole where Diana’s voice taunts him with everything he’s afraid of. Then a vision of Lucas cuts in: stop. The poison is lying to him. Diana has given him a shot at Arthur, but he has to face his fears and wake up. The scene surrounds us with our targets and makes us trigger the Burnwoods’ car bomb. To be free, we’ll have to take responsibility for what we’ve done. As 47 does it all, he envisions himself in his suit. Even in dreams, it remains the bedrock of his sense of self.

Congratulations! Congratulations! Congratulations! Congratulations!

When 47 comes around, he finds himself a subject again. Providence has stripped him to the waist and covered him in electrodes. That shows us that he’s at a disadvantage right off the bat, especially once we find out what he’ll be up against. The train he’s on, the Mortar, is a mobile black site and lab, and it’s currently on course through a Carpathian snowstorm. He’ll have to navigate cramped corridors with nowhere to hide, find passcodes, and scale the train’s frozen exterior. He’ll also face down dozens of armed Providence operatives, and like in Absolution, the visual language is clear. The Providence guards’ body armor and thick winter gear contrast with 47’s comparative nakedness. They’re as protected as he is vulnerable. Even the mechanics seem to acknowledge he’s outmatched - for once, killing non-targets won’t penalize our score. 47 is free to go on a rampage, though not all fans want to. Many find the sequence too linear, too focused on combat. Regardless, it does hammer home the David-and-Goliath theme: one man against a system that refuses to see him as a person.

Well, it took ten parts, but we finally got 47 with his shirt off.

However we may decide to deal with Providence’s heavies, we eventually reach the business-class section of the train. Here, the mood shifts again. Instead of rusty storage shelves, we find functionaries calmly typing away at their desks. This is Providence’s mother brain. They never took power through strength. They ruled through money, data, influence. We know Arthur must be close. But before 47 proceeds, he finds one more surprise: one of the staff disguises waiting on a hanger for him. He can either proceed with single-minded efficiency, or take a moment to get dressed - like in the asylum - and end things how they began. When he puts it on, we see that it’s similar to his suit - gray, a different tie, but the same vents, the same lapels. It also lets him pass undetected through the rest of the train, giving him a clear path to confront Arthur once and for all.

As always, let’s not lose our sense of practicality. IOI has left disguises at the beginning of zones before. What matters is the poetic justice of what comes afterward, when Arthur offers 47 another dose of the amnesia drug. The player can just kill him. Or, for the first time, they can choose to inject Arthur with his own serum instead. It’s a perverse mercy, one that strands him in an unmanned train car in the wilds of Central Europe with no memory of who he is. His odds seem slim regardless. But after decades of contracts, 47 now has the power to dictate whether a target lives or dies. This isn’t leaving Lenny to the vultures. It’s walking away from a nemesis - one who richly deserves a garrote - because he’s finally able to. And in that moment, 47 can reach back to his tether, a suit, to declare that it’s a choice he makes by himself, for himself.

In the year after that night, Diana makes good on her word. Providence hemorrhages members and dies in obscurity. She puts her parents’ deaths behind her and reconnects with 47, and they end up right where they started - exactly where we want them to be. They don’t need the ICA. It wasn’t what made them great. If anything, its mercenary neutrality held them back. As we leave them, they plot a new assassination game, one where they can keep those who abuse their power in check.

IOI has said that Hitman III won’t be the last Hitman game. To be honest, I wouldn’t complain if they did end it there. It’s my favorite kind of ending: one where the protagonists look forward, knowing that they still have plenty of adventures ahead. All the same, it’s a cracking sequel hook. 47 and Diana won this round, but power will always be power, so they’ll always have a job to do. How will future targets’ designs explore that? Will Diana go back to brunette? What shade will 47’s tie be next time? We’ll just have to find out.

If you’ve made it this far - first of all, I salute you. A ten-part article is a commitment at the best of times. Still, games get a bad rap for having shallow narrative, and that can lead to doubts about authorial intent. “Is this all true?” You might say. “It seems like kind of a stretch. The art team can’t seriously have put this much thought into it. You’ve wrung thirty thousand words out of conjecture and personal taste. The curtains weren’t blue because he was sad!” Well, yes. You’re probably right.

Speaking of taking yourself too seriously.

Here’s the thing: it doesn’t matter whether they did it on purpose. The symbols and cultural associations around clothes remain. I think Hitman should be proud of what it’s accomplished with costume design, and I think their example teaches us how much an outfit can say. In a medium where we’re limited by gameplay, budget, and scope, visuals communicate more than we have space for in the script. A carefully-considered outfit can elevate a character from a set of barks into a vital source of meaning. When we understand that language, we become better storytellers. Besides, if you were the world’s greatest assassin, wouldn’t you want to dress to kill?