If there’s anything you can say about Agent 47 - apart from that he’s well-dressed - it’s that he’s a hot commodity. He commands one of the world’s highest fees for his work, and he’s been nearly constantly employed for two decades. Mainly, this is because he’s so good at his job, but it’s also because the world of Hitman has so many terrible people. In the halls of government, puppet politicians scheme with secret societies to murder their way to the top. At lavish parties, armaments barons and war criminals schmooze with undercover models and auction off intel. In the tropics, drug fields flower, and enterprising grifters make a profit off of helping fellow criminals disappear. 47 has gone to Heaven, Hell, and every pit stop in between, and he’s managed to find the dark heart of humankind in all of them.

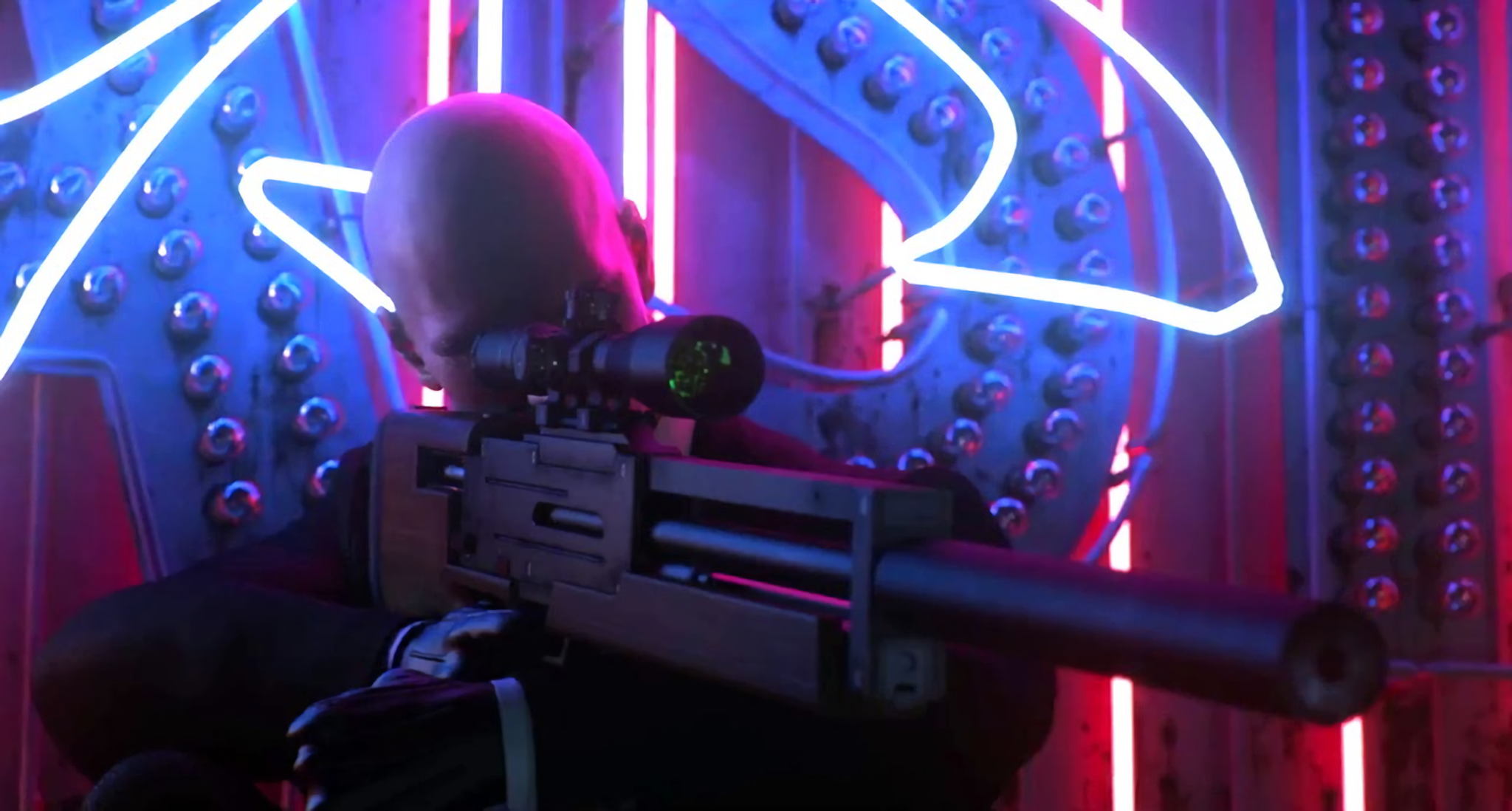

In the ‘Legacy’ trailer released to herald the reboot trilogy, Lucas Grey says that 47 has “defined the art, and it defines [him].” I’d agree with that, but I also think that the ICA’s contracts have given 47 a great palette. Game after game, IOI serves the player a cavalcade of colorful jerks to do away with. With a few exceptions, they’re wickedly easy to loathe, and at over a hundred missions, there’s a favorite for everyone. If poisoning a bratty rich-kid musician feels mundane, outwitting a rival assassin might do it for you. Their personalities don’t just provide narrative flavor, either - they inform the methods by which the player can dispense with them. As much as we love 47 and Diana, this union of writing and gameplay means the targets really define which levels we remember most.

At the beginning of the series, we see 47 pursue the kind of people you’d expect to have a hit taken out on them. Crime lords, terrorists, and other underworld denizens create a “live by the sword, die by the sword” atmosphere in the early games. Later, as his reputation grows more formidable, he hunts bigger game: the kind that cares about appearing to be good. The violence of these old spies and solipsistic billionaires is more subtle, because they have a vested interest in making their hands look clean. Regardless, all the targets hold some form of power in their social spheres, and a challenge to that power often forms the basis of their contracts. In a series about cold-blooded murder, this keeps the player’s job sympathetic and fun. There’s no poetry in cruelty, but everyone loves punching up.

So how do you dress power? And how do you dress evil? Those are different questions, and Hitman’s designers answer them in many different ways. 47 always shows up to the party in his suit, so it falls on his targets to define what kind of power and evil he’s dealing with. Some of them evoke the banality of evil, with uniforms and corporate-wear that communicate a generic, impersonal form of authority. Others portray evil as eccentric, with goofy costumes or outfits that are inappropriate for the scene’s level of formality. Still other designs focus on the decadence of evil, and this is where I imagine the designers have the most fun. They don’t have much wiggle room with a suit or a uniform. When a villain goes theatrical, they can let it all hang out.

47’s targets don’t dress in a vacuum, either. We can also learn from the clothes of the people that they surround themselves with. Hitman has drawn acclaim for its unique NPCs, and lots of them, rendering huge crowds years before other titles could get it right. Now that technology has caught up to them in earnest, they’ve doubled down, filling their scenes with strangers who create clever environmental narrative. If a level’s guard detail wears body armor and camouflage, we can guess that the target has a military connection of some kind. Put the people beside those guards in suits, and the scene becomes about defense funding. Put them in trendy party clothes, and we’re looking at a corrupt PMC. These decisions seem simple, but they affect both the games’ world and player experience: connect the dots, and you feel as canny as 47 himself.

If that depth of visual storytelling sounds impressive, it is, and Hitman has had twenty years to get good at it. Any time you have a series that runs that long, it’s worthwhile to go back to the beginning and examine how it’s evolved. Sometimes, it takes a while for a series to figure out where it’s going and how it wants to execute it. Other times, they’re aware that they want to explore a certain theme or design from the outset, and it becomes a defining feature. With that in mind, let’s go through the rogue’s gallery of 47’s legacy. You don’t become a master assassin without breaking a few eggs.

I wonder if, when Codename 47’s developers laid down their first maps and models, they had any idea what it’d become. From the minute the blood cell morphs into the bullet on the intro screen, you can tell you’re in for something that cares about its artistic vision. It’s a strange baby, rough around the edges in the same ways as the Luc Besson thrillers and Hong Kong action films that inspired it. In 2022, it’s also largely unplayable. If you can get it to run, its unforgiving difficulty and potatoey controls make you question whether the effort is worth it. But even now, you can tell it was made with love.

Trying to do a deep dive into Codename 47 presents one massive, unignorable hurdle: the graphics. It’s old. Frankly, anything before Blood Money just doesn’t lend itself to visual analysis beyond a certain level of detail. We can cross-reference Contracts - more on that later - but for the most part, the limitations of the time preclude the kind of chin-scratching that we can do with the reboot trilogy. For example, we can’t factor in the cut of 47’s suit, or the fact that his gloves look like veiny latex action figure hands. NPCs trundle around with rectangular pants and Lego hair. Remember when this was the height of realism? Gosh. We’ve come so far.

Be nice. It’s vintage.

That’s nobody’s fault. In fact, according to “Advanced Character Physics,” Codename 47 moved the needle on 3D clothes. The paper, by Thomas Jakobsen - IOI’s head of R&D - details the algorithms that they developed for the game, including ones for modeling cloth. The equations of how they achieved it are way over my head, but they clearly paid attention in a way that few others had before. In the ruthless calculus of development scope, that says something. The team felt it was important, so they allocated resources to it. So let’s set the inevitable signs of age aside and do them the courtesy of taking a closer look anyway.

On its maiden voyage, Hitman is still finding its narrative footing, unsure of its balance between grit, high drama, and dark comedy. We see some of this uncertainty play out in the NPCs, who lack what narrative designer Kris Ruff refers to as the “illusion of life.” In later installments, NPCs feel like individuals, with quirks that 47 can observe and occasionally exploit. In Codename 47, all they really have to do is present a scowly obstacle to 47’s progress. So the character design goes broad, clothing the game’s henchmen only in detailed enough outfits to identify which team they’re on. The bikers, soldiers, and color-coded triad members represent what they need to represent, and that’s about all we can say.

By contrast, the Five Fathers take the form of loud caricatures, ripped straight out of Central Casting for pulp villains. We should also acknowledge that they’re pulpy stereotypes, dated even when the game came out twenty years ago. Lee Hong gets the worst of it, with his long, upturned jacket and vest - red for the Red Dragon, naturally - evoking some kind of stage magician. His ponytail, mustache, and Dracula-esque widow’s peak plant him firmly in the bad old days of Thirties serials. Pablo Ochoa channels Scarface with his cross necklace, open shirt, and the white suit that North American movies have made shorthand for South American seediness. Arkadij Jegorov is Kazakh, not Russian, which makes a difference in the presence of his gold chain, sunglasses, and floral button-up. They telegraph crude machismo in a way that recalls regional gibes about Georgians and other Central-Western Asian groups. And while only Ort-Meyer’s name and accent give him away as German, he still dons a bow tie and lab coat. How else would we know he’s the mad scientist?

Rounding out this gang of miscreants is Frantz Fuchs, who 47 finds in a hotel shower wearing a red speedo. Nobody showers in their underwear, we all know that. It’s a contrivance because they couldn’t show him fully nude on-screen. On the surface, Fuchs’ framing shows that he has a cavalier attitude about protecting himself. He’s the least-guarded of the Five Fathers, a carelessness that 47 gamely exploits. Beyond that, the trope of “large naked man” has become a well-worn path to convey a mix of hedonism, power, and confidence. If you’re willing to meet your enemy naked, not only do you have nothing to hide, the shock and awkwardness disorients them, giving you the upper hand. I’ve heard that Winston Churchill used to hold meetings in his bathtub for this reason. Myth or fact? It’s a good story. Who cares.

Here’s what I think. I think in Codename 47, Hitman had potential in search of a voice. Because it hadn’t found one yet, it leaned on these clichés to establish its villains as men who craved power for power’s sake. The late autumn of 2000 was a less sophisticated time for video games, and in many ways, it was a simpler time for 47, too. I mean, Diana didn’t even contact him by phone back then. Ort-Meyer was working for himself. How little it mattered. How little we knew.

If Codename 47 laid out Hitman’s muscles and bones, Silent Assassin gives the series its nerves and heart. It’s as much The Godfather as a stealth thriller, and I’m not just saying that because it starts in Italy and involves a local don. In Silent Assassin, 47 tries to leave killing behind, and learns very quickly that he was foolish to ever think he could. A mysterious mastermind doesn’t take kindly to him being out of the game, so he kidnaps the old priest who’s taken 47 under his wing. To gather the resources to save him, 47 has to re-enmesh himself with the ICA and play right into his enemy’s hands. The story offers him a dark choice: surrender, or continue allowing the underworld to endanger innocents in its effort to drag him back in. In the end, 47 resigns himself to his genetic destiny and takes the mantle back up. He should have known it was all he was good for.

Some fans find the high-gloss spy tropes of the new trilogy out of step with the tone of earlier Hitman entries. I think Silent Assassin already shows an interest in them, as well as the messy ways that they intersect with 47’s personal life. Take the third mission. We find 47 in St. Petersburg. He doesn’t want to be there, but he’s at the mercy of the ICA’s Faustian deal. The target: an ex-KGB officer. The scene: a secret meeting. The optimal kill: sniping him from a window across the square. It’s a love letter to The Day of the Jackal, and it shows that Hitman’s ambitions have grown. From there, instead of nukes on boats or casually-researched jungle gods, 47 tangles with Spetsnaz and stolen military software. The scenes are still thriller set pieces, but Silent Assassin plays down some of Codename 47’s fantastical elements in favor of grounding itself in the real world.

That said, at this stage, most of the costumes continue to follow Codename 47’s broad thematic trends. Don Guilliani hearkens back to every mafia movie ever, complete with the spectator shoes and suspenders. (And the gun. No cannoli, though.) Hannelore von Kamprad’s cat-eye glasses also look to the past, this time to evoke sadistic prissiness. She may be a doctor, but there’s more than a little Nurse Ratched in her. The Russian generals wear their service dress uniforms, the details of which get a little more interesting. Though their blue cap bands correctly correspond to the KGB, I’m not sure they’d still wear them in the post-Soviet era. That’s not me being coy - I genuinely don’t know. Either way, it seems risky to wear your uniform to a clandestine arms deal. For that, you might as well paint a target on your back and go, “Hey, intelligence community! Photograph me! Russia is up to no good.”

The difference is, in Codename 47, that felt like getting the job done. In Silent Assassin, it feels intentional. Silent Assassin is a deeply symbolic game, and it goes for its operatic atmosphere with full-throated earnestness. With its choral music and fervent religious overtones, it needs character designs that land all the way in the back row. Once you see it as theater, realism doesn’t seem to matter as much. It’s not whether the clothes are logical. It’s what they represent. In their outfits, the targets convey worldly evil - arms races, organized crime, sensual decadence. Father Vittorio’s cassock doesn’t just show us he’s a priest, it makes him the manifestation of 47’s desire for grace. It’s a great thematic gambit, which makes it all the more frustrating when it steps in some of the same potholes that Codename 47 did. Maybe harder. The Deewana Ji levels drew so much controversy for their parallels to the 1984 Sikh Massacre that IOI went back and amended them. Again, we stumble over the limits of Hitman’s imagination, when it’s already shown us that it’s capable of more.

And of course, we can’t forget Sergei Zavorotko, the architect of the plan. He’s Arkadij Jegorov’s brother, but he hasn’t inherited his brother’s tropes. Instead, there’s something Metal Gear about him, between his long hair, mutton chops, handlebar mustache, and flapping, upturned lapels. (The wiki says he was based on the villain from the 1996 film Eraser, so it sounds like IOI and Hideo Kojima were watching similar movies.) The “leather coat and turtleneck” look is a classic, and one we’ve come to expect from the fictional scoundrels that seem inexorably drawn to war. It’s all-weather, vaguely military, but not a uniform. It tells us he hangs out with generals, but he’s not one of them. Though the game calls him a “crime lord,” we know he’s no ordinary thief-in-law. He’s here to peddle nukes to world powers, and he’s dressed the part.

As a sidenote, Zavorotko is one of 47’s sturdiest targets. Even a sniper shot may not bring him down in one hit. I’m not saying he’s an actual Metal Gear boss who wandered off the set, but I’m not not saying that, either. Who knows? Ort-Meyer would totally do nanomachines. We’re getting off-track, though. 47 has a lot of work ahead of him, and his enemies will only get more powerful from here.