At the dawn of 2004, Hitman has two outings under its belt, enough to put down roots in the growing field of stealth games. And boy, is it growing. Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell franchise has just shipped its second game. The seminal Thief will soon ship its third. In November, the aforementioned Metal Gear series will release Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater and define the genre for years to come. Even Sly Cooper has reimagined the genre for kids! Everyone wants a piece of the stealth pie. Secrecy, it seems, is on-trend.

Yet Hitman still stands apart, a quirky, contemporary character among its hooded, midnight-cloaked, and camo-painted peers. It has a bloody, corrupt world, rich in lore and scenery. It has a protagonist that already feels developed and a story with room to evolve. It’s even settling nicely into its aesthetic niche. As we’ll see in the next three titles, it’s just getting warmed up.

Hitman: Contracts occupies a funny narrative space. It’s not a straight-ahead remake. It’s not completely new. It takes place partly after Silent Assassin and partly during Codename 47. It will become an off-screen interlude in Blood Money. Apart from the ending, it basically happens in a dream, a storytelling device that we’ve been ridiculing for decades. After thwarting arms deals and terrorist attacks, it pits 47 against a crooked cop with a grudge and a megaphone. In today’s industry, a publisher might look at its surreal framing and wiggly chronology and label it a risk.

And yet it works. If there was any risk to Contracts, it paid off, because Contracts is where many believe Hitman comes into its own. Not many people still play Codename 47. You will find some who replay Contracts, and I think that’s due as much to its story as its next-gen ports. On the series’ third lap, we see what happens when one of 47’s contracts goes wrong. He’s shot, hiding in a hotel room, and feeling more than a bit unwell. As he waits for an ICA medic to come to his aid, he remembers - or hallucinates - some of the missions that got him there. Contracts has figured out how to marry the events of the first game with the mature tone of the second, and in doing so, it’s found its groove. To this day, fans point to levels like Beldingford Manor and The Meat King’s Party as their favorites of the series.

Which is curious, because levels like The Meat King’s Party introduce us to what I like to call Weird Hitman. Hitman has always flirted with eccentricity, but Contracts is the first time the series dares to go this, well, bizarre. Right from the outset, the game sends 47 to a serial killer’s gala in a Romanian slaughterhouse. It feels like such a spiritual sibling to the Hostel series that I had to check when the first movie came out. (For the record, Contracts came first.) Next, we head to a Kamchatka whiteout full of references to The Thing, a gothic English country house, and other eerie nighttime scenes. Were the slaughterhouse halls really spattered with that much gore, or is 47 just getting loopy from hypovolemic shock? The game doesn’t answer. If Silent Assassin was mob opera and Codename 47 was action pulp, Contracts is Hitman-does-horror, and not knowing is always scarier.

So it falls to Contracts’ new targets to anchor that sense of nightmarish not-quite-reality. This is where I think their experience with Silent Assassin paid off. They knew how to go theatrical, and they were game to do it again. We find Lord Beldingford in his pajamas, but his son, Alistair, holds court in a deeply traditional English riding costume. Sure, it’s a hunt weekend, but those are typically morning clothes, and the kind of people who’d wear them are the kind of people who’d change for dinner. For Alistair, the hunt never stops. This adds some bloodthirst to his smarm, and it hints at the most dangerous game that’s really going on at the house. Back in Romania, Andrei Puscus’ demonic mask and red dress shirt play on the well-trodden “devil lawyer” stereotype. (Unfortunately, there’s no charitable read on his client’s design.) And Rutgert van Leuven may just be a biker, but couldn’t you see him in a Rob Zombie movie? Rub some dirt on him.

When the medic shows up to operate, 47’s memories change course, and Contracts pivots to six streamlined remakes of Codename 47 missions. The new versions of 47’s genetic donors don’t look that different - Lee Hong is basically the same, and Frantz Fuchs is exactly the same. But because we have their original versions to compare them to, we can still find a few places where IOI has tweaked them in the service of realism. Arkadij Jegorov has taken a hit to his hairline, and his shirt collar and chains have shrunk, dialing back some of the cartoonishness. Fritz Fuchs has traded his speedo for trunks, and he’s also lost the floppy hair that once loudly recalled a certain Austrian dictator. It’s a lot to read into a gold chain and a haircut, but I like to think it shows how IOI’s sensibilities have changed.

However, there’s one familiar face from Codename 47 who receives a more dramatic revamp. Contracts features the return of Mei Ling, the canny brothel girl who gave 47 his first kiss. (The series waffles on her name, calling her Lei Ling in the first two games and Mei Ling in Contracts. Fans tend to call her Mei Ling, so let’s stick with that.) Codename 47 dressed Mei Ling in a low-cut tee and miniskirt, plain even by the standards of the game. Obviously, real women in her line of work wear all kinds of clothes. Still, let’s be honest: something about her first look says “laundry day.” Contracts reimagines her Codename 47 outfit as thigh-high stockings and a mini-dress with frog closures. At first, these closures appear to strain against her bust, but closer inspection reveals that they don’t - they’re just cut long in the chest. That suggests that the dress is designed to be worn open, with fully-exposed cleavage, instead of closed like normal frogs. This identifies it unambiguously as a fetish costume, which seems closer to the mood they wanted her scenes to evoke.

It’s not the kind of detail I expect the franchise to address, but I’ve always been curious about what happened to Mei Ling. Did she go back to Hong Kong and take over the triads? Did she marry the right old man and retire as a rich widow? Or did she channel her memory for numerical codes and honey-trap skills into an intelligence career of her own? Wouldn’t that be something. I’m rooting for her.

You can’t talk about Hitman without talking about Blood Money. For many fans, it set a standard of narrative and gameplay that the series had never met before. To some, they’ve never matched it since. I can see why they’d say that. Blood Money rolls off the back of Contracts with confidence. It knows what it wants to be, and how it wants to execute it. Its story continues from Contracts, too. After dealing with the GIGN, 47 and Diana realize that a rival agency is after them. As 47 evades them, he finds himself trapped in a scandal involving a cloning bill and an FBI director bent on exposing him. In returning to cloning, it returns to the series’ sci-fi roots, but weaves them into a web of ever-more-plausible political intrigue.

And Blood Money is big. It may not match Silent Assassin’s level count, but the maps feel larger, and the missions have become more elaborate. While earlier games were still sandboxes, in practice, it often felt like there were only one or two feasible ways to get out with your score intact. In Blood Money, alternate assassinations become more viable, and this opens up hours of exploration and creativity. It’s also 2006 now, and technology has advanced enough that Hitman can start developing the NPC diversity that it will become famous for. From Margeaux LeBlanc’s cheap wedding gown to Mrs. Stewart’s prim pink suit to the Sinistras’ pool boy, the world of Hitman has found its spark of life.

That means there’s a lot of ground to cover. In short, Blood Money settles comfortably into the niche that they’ve been building since Silent Assassin with its target designs. They’ve got the rhythm down. A few tongue-in-cheek references - Lorne de Havilland to Hugh Hefner, Fernando Delgado to Pablo Ochoa himself. A few silly ones - Vinnie Sinistra’s Miami Vice shirt, Skip Muldoon’s hat, the Murder of Crows costumes that will inspire the series’ later memeworthy mascot kills. We even see the return of Weird Hitman: Vaana Ketlyn and Anthony Martinez’ devilish costumes have since become icons of Hitman’s edgier days. (The game goes deliciously meta with its opera level, too.) A good deal of the rest are just guys in businesswear, and while that’s not riveting essay material, from a worldbuilding standpoint, it makes sense. Hitman has found the costuming philosophy that it will play to the hilt in the reboot trilogy: the men who buy and sell the world dress like everyone else.

Blood Money also gives 47 his first real adversary in Mark Parchezzi III, a clone created by the shadowy Franchise. He’s already in disguise by the time 47 meets him, but in promotional renders, he wears a white suit of the exact same cut as 47’s. See, in Western culture, we’re used to the white-hat-black-hat coding of good guys and bad guys. We’ve been exposed to it since silent cowboy movies - it’s deeply culturally ingrained. Over time, more and more stories have subverted that, and Blood Money does it to the same sinister effect. White can symbolize light, but it can just as easily speak to sterility, coldness, or a false veneer of good hiding a dark secret. As 47 and Mark square off with parallel intensity, they feel like chess pieces, pawns of their respective agencies.

Ultimately, the white suit positions Mark Parchezzi III as 47’s equal. If only he really were. 47 is handsome, but indistinct. His features fade from people’s memories. If he’s noticed his gift of slow aging, he doesn’t seem fazed by it. Mark’s albinism - like his brother, Mark Purayah’s - guarantees that he’ll stand out, and he rages against the rapid aging that has given him months to live. He knows he’s an imperfect reflection, which adds a note of tragedy to his quest to one-up 47. It’s practically Grecian: a clash of hubris, desire, and fate.

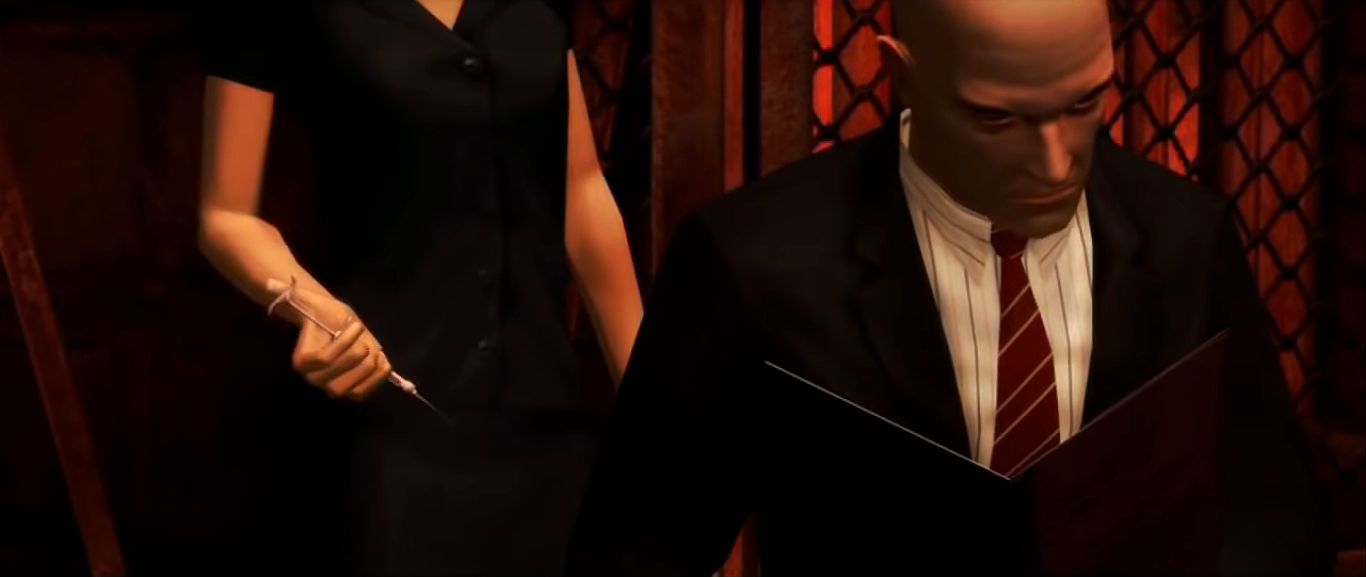

Finally, Blood Money marks the first time that Diana appears on-screen in any significant capacity. I’m going to take a detour here, because as the series’ deuteragonist, her scenes establish a huge amount of worldbuilding and tone. In Diana’s first real camera role, we never see her face head-on. The cutscenes go to great pains to hide her from the neck up behind unconventional camera angles and a wide-brimmed hat. Not only does it hearken back to the film noir that sometimes sneaks into the corners of Hitman, it keeps her motives obscure. Because Diana has a twist coming, a gambit that she’ll repeat in the olive grove in Mendoza, but we don’t know that yet. For her to pull it off, 47, antagonist Alexander Leland Cayne, and the player themselves need a sense of ambiguity about where her loyalty really lies. If we’d seen her face, something, no matter how subtle, might have given her away. We don’t, and Diana has the power to take us off guard when she jabs that serum into 47’s neck.

With no facial expressions to go on, we have to get to know Diana through her mission briefings, dialogue, and - you guessed it - her clothes. She’s infiltrated Alexander’s inner circle as his nurse, wearing a simple black ensemble that resists any specific trends. Again, we have kind of a graphical problem, but it’s either a matching skirt and blouse or shirt dress, a staple that everyone from diner waitresses to midcentury stars have worn. While it doesn’t say “you can bleed on this” in the way we might expect from a nurse - Marta from Knives Out comes to mind - it’s not totally implausible. I’d wager she can machine wash it, and its flexible level of formality means she never looks out of place, even at a funeral. Diana knows the situation with Alexander will turn on a dime, but not when, so she’s chosen maximum practicality without skimping on style.

The way Diana accessorizes the outfit does more to suggest that she’s not just at Alexander’s side to fiddle with his IV. Before, we could have chalked Diana’s enigma up to ICA protocols, a safeguard in case of an agent-handler compromise. But as soon as we see her in that hat, we know that, protocols or no protocols, she enjoys being a woman of mystery. And she’s not afraid to make sacrifices for glamour, either - instead of walking shoes, she finishes the look with a pair of ankle-strap heels. I admit, I bring these up in part to poke fun at them, because someone in the IOI art department loves ankle-strap heels. Almost every woman in Blood Money wears them. They’ve remained a staple of Diana’s outfits throughout the series. I’m not judging! It’s just one of those things you notice when you’ve been a fan long enough.

You want to hear a secret? I’ve always wondered whether they put ankle straps on the shoes to cover the 3D models’ leg seams. It’s not unheard of for character models to have strategically-placed neck, wrist, or ankle details to hide a pesky break in their skin. I admire the ingenuity. Even Hollywood uses gaffer tape. That’s why the 3D people have their jobs, and I write about them from the cheap seats.

Oh, Absolution. If you define “art” as something that provokes emotion in the viewer, Absolution is a bona fide work of Molly Ivins “ort.” I know most of it is set in South Dakota, but like a Texas armadillo statue, it still looms large over many fans’ opinion of the series. When Diana sabotages the ICA, 47 is sent to retire her, and learns that she did it to protect Victoria, a killer clone like him. To save the girl, 47 goes on the road trip from hell, tangling with mercs, crooked lawmen, and… Danny Trejo on steroids? Just kidding. It’s a shame, because for me, Absolution marked the first time in the series that the gameplay felt satisfying and fun instead of stressful. Thankfully, 47’s aim-flick-bonk throwing skills and suspicion arrows live on in the reboot trilogy.

For what it is, Absolution leans into its costume design like a champ. You can smell the dust that settles on the jeans of the Hope Cougars. Blake Dexter’s boxy, two-tone suit, cream cowboy hat, and bolo tie hit “bullish Texas entrepreneur” right on the nose. (Again, yes, we’re in South Dakota, but later data suggests that his origins lie farther south. Think he moved there to avoid taxes? The Panama Papers would back it up.) Benjamin Travis’ sloppy look speaks of a managerial career gone to seed, absent of the military discipline that got him there in the first place. By contrast, his ICA soldiers are quintessential tacticool thugs in their chunky body armor. Don’t listen to the barks. They don’t intend to bring 47 in alive.

As I mentioned, Absolution also takes us behind the scenes of 47’s suit for the first time. Which is ironic, because his Absolution suit sits oddly on him. The Absolution suit looks fine in the new trilogy, but in its original game, it gives 47 small, sloping shoulders and a squarish torso. That’s the first thing Tommy should have measured for. If a jacket doesn’t fit in the shoulders and chest, you’ll have a devil of a time making it fit anywhere else. The jacket collar stands away from 47’s neck, which means it’s too big, and the pant waistline sits lower than normal, which makes his legs look short. Not that you may see much of it. In Absolution, keeping 47 in his starting outfit can prove to be more trouble than usual. Almost every zone features NPCs that attack on sight - 47 is the hunted here, not the hunter, and he has few avenues to progress. Unless you’re going for a Silent Assassin Suit Only run, you’re better off grabbing a disguise as soon as possible. I have to give 47 credit where it’s due: he wore that Tiki bathrobe without so much as a flushed ear.

Then there are the women. Layla’s visible bra - a dark bra under a white blouse. Hmm! - is racier than your average executive assistant, and that’s before she strips down. Jade Nguyen’s glasses, midriff jacket, and miniskirt put the same “naughty secretary” spin on the ICA dress code. It’s hard to picture Diana in that, although, to be uncharitable, she spends most of her Absolution time lying naked on the floor. The minor NPCs share a similar fate, from the employees of the obligatory strip club level to Mrs. Cooper’s latex ensemble and Lilly’s tiny peasant top.

It’s easy to fall into a superficial loop of “Look at that one! And that one!” here, because their designs have a singularity of narrative purpose: sleaze. And it’s not like Hitman was never sleazy before. It’s the underworld. At least one assassin in angel crotch tape is par for the course. It’s the lack of variety. Absolution has more cheesecake than the previous games combined without a Margeaux LeBlanc or Mrs. Stewart to offset it. (The closest it gets is Sister Mary, whose habit looks pretty accurate, presumably because her job is to be motherly and get shot.) The result is a game world so shady that even 47 is a little foreign to it. I bet he never thought he’d miss the Mississippi weeds.

On a good day, I guess you could argue that the aesthetic dissonance in Absolution is the point. 47 is having a rough time. For once, he’s powerless: unmoored from Diana, on the run from both sides of the law, and in search of a teenager that he has no business being responsible for. His suit itself goes through the wars. The fitting problems I mentioned earlier are common when you buy from generic menswear stores, and they could underline 47’s situation - battered, scraping by on the minimum. If the whole thing feels like an awkward mismatch, it’s because he’s in a situation where he doesn’t belong. I’ll even retract my earlier skepticism and say that if you follow that train of thought far enough, it almost justifies the Saints. The vanity project of an eccentric division chief, a group likely redacted and coughed about in the boardroom after his death? Okay. I’ll go along with it, in the way that I patiently go along with Margot Robbie’s feet in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

I mean, almost.

So there’s no question that Absolution has the grindhouse fashion sense down pat. The question is whether that sense works for a Hitman game, and from the fans I’ve spoken to, the consensus is that it does not. IOI seems aware that Absolution sticks out like a sore thumb, and has decided that - in true IOI fashion - it’s best to have a sense of humor about it. Diana mentions in an offhand line to Tamara Vidal that Blake Dexter’s assassination happened in “a parallel universe.” Can you blame them? I don’t, especially not after working on a studio game and learning about Absolution’s development cycle. Forget politics. Gamedev is the real art of the possible.

Regardless of whether or not I absolve it for its sins, after Absolution, IOI stood at a decision point. Many felt that they had strayed from Hitman’s original vision, in style, narrative, and gameplay. They had a lot of trust to win back. Their next move would prove to be a razor-sharp course correction that cleaned out 47’s closet and catapulted him all the way to the top.